"The game is up"

Published:

Categories:

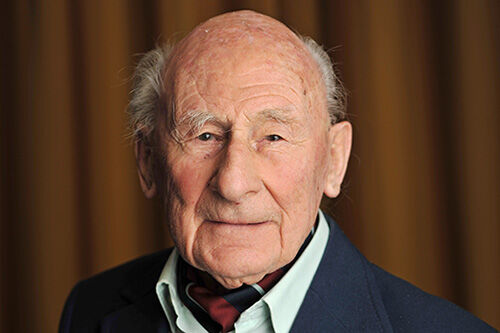

As the PoWs began to escape through the tunnel on the night of 24 March 1944, it was a long wait for the late Jack Lyon as he stood in the queue in Hut 104. In an interview before his passing, Jack told us about that historic night and the eventual discovery of the tunnel by the guards.

It was a moonless night on the evening of 24 March 1944 – the best conditions in which to attempt an escape from Stalag Luft III. At around 10.30pm the first men made their way through the tunnel. With the tunnel mouth some 15 feet short of the tree line and within 30 yards of the nearest watch tower, the chance of detection was high but Squadron Leader Roger Bushell knew the plan had to go ahead. A length of rope was used to signal to the men below when the coast was clear.

Jack said: "As soon as we reached Hut 104 we were allocated a place in one of the rooms and told not to move until we were called, and so we remained until the discovery in the early hours of the next morning.

"The camp lights went out when the air raid sirens sounded and we were then in total darkness. We didn't talk – we didn't want the guards to suspect anything but I wasn't nervous.

"I was waiting in the queue for quite a few hours when I heard a single shot and that meant that the odds were that the tunnel had been discovered and the goons would be here pretty shortly.

"We set about destroying anything incriminating like maps, compasses, ID cards and above all German currency. It was a serious offence to hold German currency. It was the only time I ever burnt money, I can assure you!

"We waited and not long after the guards arrived in the hut and we were herded onto the parade ground, searched and stripped to our underwear. It was just after dawn and a bitterly cold night. Bitterly cold.

"Of course our spirits were very low. The thing I remember – etched indelibly on my mind – is the attempt by two prisoners to indulge in a bit of horseplay – the idea being to either confuse or prolong the counting of the remaining prisoners and to help those who may have escaped.

"Von Lindeiner-Wildau, the commandant, who was obviously furious and already aware the escape would terminate his command, said he would personally shoot the next officer who moved. The effect was salutary. Later on we were allowed to return to our huts and, as you say, the rest is history.

"It must have been at least ten days later before we discovered what happened to the recaptured officers. We couldn't understand why the Germans seemed almost at a loss afterwards.

"They closed the cinema as a reprisal, but there weren't any other serious repercussions – they weren’t foaming at the mouth and we couldn't work out why. And I think the reason was they had heard what had happened to the escapees and many of them felt great shame because they knew such an act would inevitably tarnish the reputation of the Luftwaffe.

"When the news came through of the murder of the 50 – 47 first of all and then later another three names were posted – it was then that we realised why they had seemed so constrained.

"I received a punishment, a sentence, of 28 days solitary confinement. But that was a punishment I never suffered because the list for the cooler was too long!

"It was a costly operation but not necessarily unsuccessful. It did do a lot for morale, particularly for those prisoners who'd been there for a long time. They felt they were able to contribute something, even if they weren't able to get out. They felt they could help in some way and trust me, in prison camps, morale is very important."